Evaluation of EU legal framework and policy

on arms exports in the context of the war in Yemen.

It should be clear from the preceding chapters that the war in Yemen is fought with a lot of European weapons. Military materiel from European origin is a key enabler for the warfighting capacity of Saudi Arabia and the UAE, as well as for some of the contributions of other participating states. Some of these arms have been exported long before the military intervention in Yemen started, but after the start of the war new materiel has been delivered or contracts have been signed. Further, the European arms industry plays an important role in sustaining this war through the delivery of ammunition and by providing maintenance for the earlier exported and now deployed equipment.

This situation seems in sharp contradiction with the existing legal framework.

The Arms Trade Treaty

The main international legal instrument regulating arms trade is the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT), adopted in 2013 and in force since 24 December 2014. The Arms Trade Treaty prohibits arms exports when they contribute to war crimes and violations of international humanitarian law (IHL).

Article 6 of the ATT stipulates:

- A State Party shall not authorize any transfer of conventional arms covered under Article 2 (1) or of items covered under Article 3 or Article 4, if the transfer would violate its relevant international obligations under international agreements to which it is a Party, in particular those relating to the transfer of, or illicit trafficking in, conventional arms.

- A State Party shall not authorize any transfer of conventional arms covered under Article 2 (1) or of items covered under Article 3 or Article 4, if it has knowledge at the time of authorization that the arms or items would be used in the commission of genocide, crimes against humanity, grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions of 1949, attacks directed against civilian objects or civilians protected as such, or other war crimes as defined by international agreements to which it is a Party.

Article 7 of the Arms Trade Treaty further obliges states to conduct a risk assessment in which it has to "assess the potential that the conventional arms or items:

- would contribute to or undermine peace and security

- could be used to:

- commit or facilitate a serious violation of international humanitarian law;

- commit or facilitate a serious violation of international human rights law;

- commit or facilitate an act constituting an offence under international conventions or protocols relating to terrorism to which the exporting State is a Party; or

- commit or facilitate an act constituting an offence under international conventions or protocols relating to transnational organized crime to which the exporting State is a Party."

When this assessment determines that there is an “overriding risk” of any of these negative consequences, the exporting state “shall not authorize the export”.

In other words, states are under an obligation not to export arms when there is an overriding risk that the arms could be used in serious violations of international humanitarian law and international human rights law and to conduct a risk assessment to establish if this is the case. Not properly conducting a risk assessment or authorizing export even after concluding an overriding risk would lead to a violation of the ATT by the exporting state.

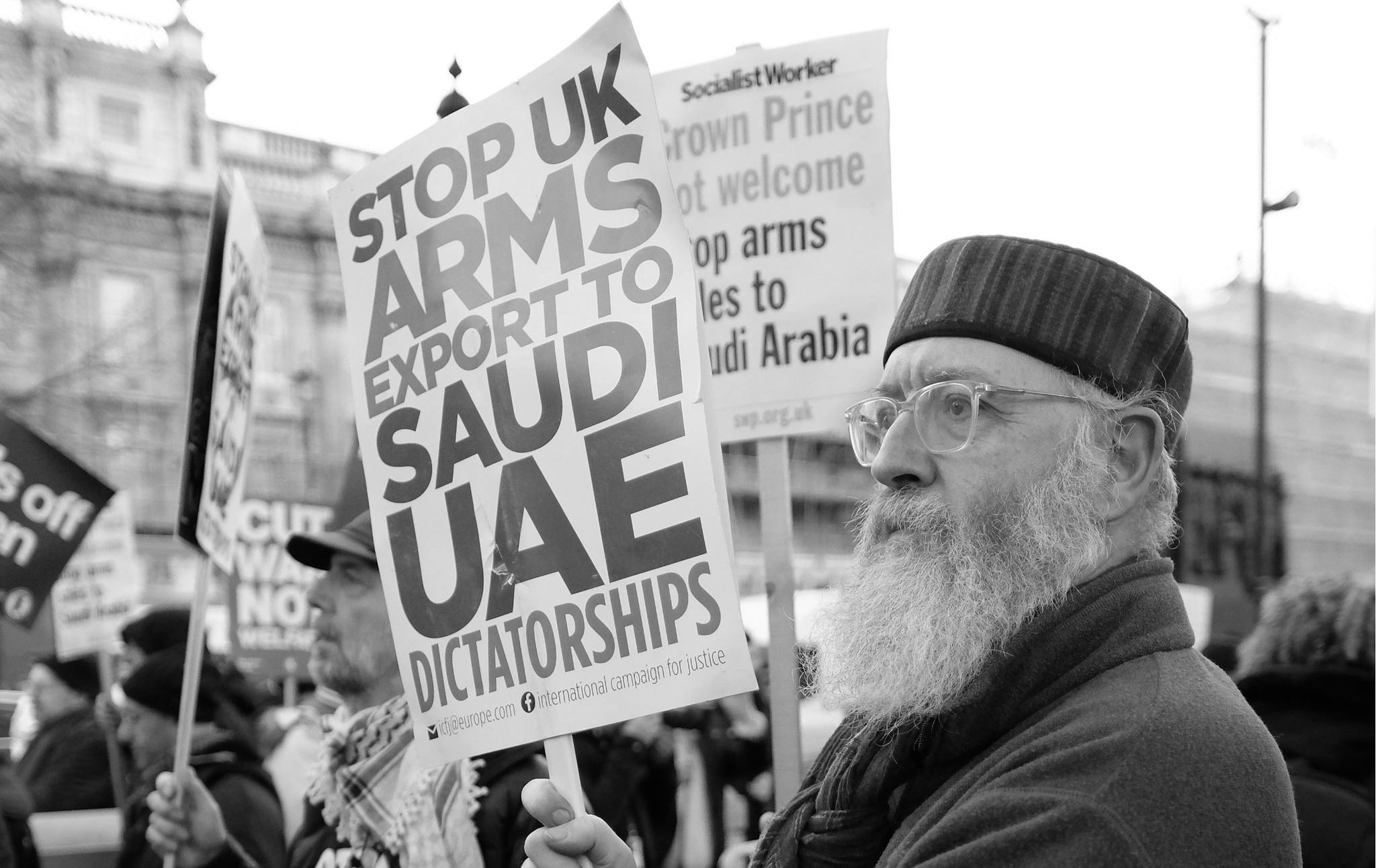

image: Alisdare Hickson [CC BY-SA 2.0]

The Geneva conventions

International law also contains other obligations and limitations to export arms to states and groups in armed conflict, often preceding the ATT.

According to Article 1, common to the 4 Geneva Conventions, states have the duty not only to respect the Conventions, but also to ensure their respect, in all circumstances. This obligation is not limited to the parties in the conflict, but also to other states. It is now part of customary law and extends to all international humanitarian law. What this obligation entails depends on the influence a state has on the parties in the conflict.

The Group of Experts appointed by the UN Human Rights Council to monitor the situation of human rights in Yemen makes clear that this obligation to ensure respect requires that states refrain from transferring weapons if there is an expectation that these weapons would be used to violate international humanitarian law. It further states that this obligation requires an assessment to be made prior to any arms transfer.1 The ATT mentions this obligation in its Preamble as one of the principles on which it is based. Article 6 and 7 ATT can therefore be seen as an implementation of this earlier existing general obligation.

The Common Position

The EU has itself agreed to Common Position 2008/944/CFSP of 8 December 2008 defining common rules governing control of exports of military technology and equipment, which replaced the Code of Conduct on Arms Exports from 1998 with similar content. This Common Position details how this assessment should be done and contains 8 criteria to assess whether a licence should be refused.

Criterion Two concerns the “Respect for human rights in the country of final destination as well as respect by that country of international humanitarian law” and states:

“Having assessed the recipient country’s attitude towards relevant principles established by instruments of international humanitarian law, Member States shall:

- deny an export licence if there is a clear risk that the military technology or equipment to be exported might be used in the commission of serious violations of international humanitarian law.”

Criterion Four concerns the “Preservation of regional peace, security and stability” and states:

“Member States shall deny an export licence if there is a clear risk that the intended recipient would use the military technology or equipment to be exported aggressively against another country or to assert by force a territorial claim. When considering these risks, Member States shall take into account inter alia:

- the existence or likelihood of armed conflict between the recipient and another country;

- a claim against the territory of a neighbouring country which the recipient has in the past tried or threatened to pursue by means of force;

- the likelihood of the military technology or equipment being used other than for the legitimate national security and defence of the recipient;

- the need not to affect adversely regional stability in any significant way.”

Criterion Seven further concerns the “Existence of a risk that the military technology or equipment will be diverted within the buyer country or re-exported under undesirable conditions”.

image: Felton Davis [CC BY 2.0]

None of the warring parties in Yemen have shown much respect for their obligations under international humanitarian law or under human rights law and the humanitarian consequences have been devastating.

The military equipment originating from the EU has been supplied to the Saudi- and UAE-led coalition. Although the military intervention as such is not a violation of international law (as it happened on demand of the government of Yemen), the actual conduct of the intervention by the coalition shows a persistent patterns of violations of international humanitarian law. It is therefore difficult to understand how EU member states can still export large amounts of military equipment and find such export compatible with respect of their obligations under international humanitarian law and the Arms Trade Treaty or with their internal rules on arms export in Common Position 2008/944/CFSP.

This observation is shared by the Group of Experts of the UN Human Rights Council. It concludes:

“As in many other conflicts, it appears that common Article 1 to the Geneva Convention is not sufficiently considered by third States that are not directly involved in the conflict in Yemen, in particular those that exert or may exert a specific influence on the parties to the conflict. More specifically, it is questionable whether the United Kingdom, the United States, France, and the Islamic Republic of Iran are taking all reasonable measures to ensure the respect for international humanitarian law in Yemen. The same may be said for all States that transfer arms to the parties to the conflict in Yemen. With the number of public reports alleging and often establishing serious violations of international humanitarian law, no State can claim not to be aware of such violations being perpetrated in Yemen. As evidenced in the reports of the Group of Experts, parties to the conflict in Yemen have been committing violations that may lead to criminal responsibility for numerous war crimes.”2

It further warns that arms exports in these circumstances can make the exporting state liable for violations of the ATT and IHL.

Given this obvious contradiction between the arms exports by EU member states to the Saudi-led coalition and the conduct of this coalition in the armed conflict in Yemen, we can wonder if these exports are not in violation of the EU Common Position 2008/944/CFSP and of article 7 of the ATT. In the case of states which have obtained detailed intelligence of the actual conduct of coalition operations or which provide also direct military assistance or support, especially the UK but also France, it can also lead to a violation of article 6 ATT and even to liability for participating in war crimes and serious violations of international humanitarian law.

Although the licencing process should entail an assessment of the elements mentioned in article 7 of the ATT, the blatant disregard for IHL shown by the Saudi-led coalition demonstrates that these arms exports are happening without making a serious assessment of the criteria in the Common Position and article 7 of the ATT. It shows that the licensing process in most EU member states remains a form of window dressing or is at least totally ineffective due to a serious lack in quality.

The ICRC guidance for applying IHL criteria in arms transfer decisions mentions three main categories of indicators and states:

“A thorough assessment of the risk that the arms or military equipment transferred will be used in the commission of serious violations of international humanitarian law should include an inquiry into:

- the recipient’s past and present record of respect for international humanitarian law;

- the recipient’s intentions as expressed through formal commitments; and

- the recipient’s capacity to ensure that the arms or equipment transferred are used in a manner consistent with international humanitarian law and are not diverted or transferred to other destinations where they might be used for serious violations of this law.”

The EU User's Guide to Common Position 2008/944/CFSP includes this text from the ICRC Guidance. Both develop these elements into a range of relevant questions.

We cannot make a detailed assessment of all arms transfers within the scope of this report, but it should be clear that the coalition members have compiled a very poor record with regards to respect for international humanitarian law. This record includes the following violations of international humanitarian law:

- indiscriminate attacks and targeting of air strikes.

This has been widely documented by several human rights organisations and by the UN HRC Group of Experts. The Group of Experts states:

“In the first year of its mandate, the Group of Experts analysed a number of emblematic coalition airstrikes in the context of the broader patterns exhibited by the strikes. In the incidents investigated, it found concerns with coalition processes and procedures for target selection and execution of airstrikes based upon the apparently disproportionate impact on civilians. The Group further investigated emblematic airstrikes carried out over the past year. Despite reported reductions in the overall number of airstrikes and resulting civilian casualties, the patterns of harm caused by airstrikes remained consistent and significant.” (A/HRC/42/17, §24)An obvious example of indiscriminate targetting was the Saudi declaration of the whole of the cities of Saada and Marran as a military target. - indiscriminate shelling.

The use of direct and indirect fire weapons with wide-area impact in civilian neighbourhoods amounts to indiscriminate attacks and is a serious violation of IHL. The Group of Experts states:“The Group of Experts found reasonable grounds to believe that the Yemeni armed forces and affiliated groups, including armed groups backed by the United Arab Emirates, were responsible for serious violations of international humanitarian law for having launched indiscriminate attacks due to the weapons used and the locations, regardless of whether there was a military objective in the area. These acts may lead to criminal responsibility for war crimes.” (A/HRC/42/17, §41) Also Saudi military forces have conducted indiscriminate artillery attacks, mainly in the Saada province. - The naval and air blockade, leading to severe limitations and even blocking of the import of humanitarian aid and life necessities.

The Group of Experts states in its first report:“58. There are reasonable grounds to believe that these naval and air restrictions are imposed in violation of international human rights law and international humanitarian law. The Government is required to achieve progressively the full realization of the economic and social rights of the people in Yemen and to at least ensure satisfaction of minimum standards of these rights. The Government and the member States of the coalition must also allow and facilitate rapid and unimpeded passage of humanitarian relief. Given the severe humanitarian impact that the de facto blockades have had on the civilian population and in the absence of any verifiable military impact, they constitute a violation of the proportionality rule of international humanitarian law. The effective closure of Sana’a airport is a violation of international humanitarian law protections for the sick and wounded. 59. Such acts, together with the requisite intent, may amount to international crimes. As these restrictions are planned and implemented as the result of State policies, individual criminal responsibility would lie at all responsible levels, including the highest levels, of government of the member States of the coalition and Yemen.” (A/HRC/39/43) - Attacks against objects indispensible to the survival of the civilian population and the use of starvation as a method of warfare.

The Group of Experts states:“All parties to the conflict used and conducted attacks against objects indispensable to the survival of the civilian population. Coalition airstrikes notably destroyed or damaged farmland, water facilities, essential port infrastructure and medical facilities.” (A/HRC/42/17, §52)“In both international humanitarian and criminal law, starvation covers the deprivation or insufficient supply of food, water and indispensable non-food items, such as medicines. It remains to be established whether the parties have intentionally used starvation to advance their military aims. However, the fact that the acts described above all played a role in depriving the population of objects indispensable to its survival, and have been continued, justifies deep concerns that starvation may have been used as a method of warfare by all parties to the conflict. Such deprivation also amounts to prohibited inhuman treatment. Considered serious violations of international humanitarian law, these acts may lead to criminal responsibility for war crimes.” (A/HRC/42/17, §56)

A wide range of human rights violations by coalition forces and their allied militias have been observed as well:

Furthermore, the warring parties are observed to recruit child soldiers:

These observations of serious violations of IHL and human rights are not isolated incidents, but show a persistent, ongoing pattern of IHL and human rights violations by coalition forces. Further, the Group of Experts shows the inadequacy of the internal processes of the coalition members to address IHL violations.

Also, the obstruction by the coalition members and the government of Yemen of the work of the UN HRC Group of Experts is an indication of the coalition members unwillingness to address their IHL violations. Therefore there is no reason to assume that the respect for IHL by the coalition troops will improve. Rather it has to be assumed that this pattern of IHL violations will continue.

image: © Frederik Sadones

When we pause to look at this pattern of widespread and serious violations of IHL and human rights, it becomes impossible to understand that EU member states are still able to conclude the absence of “a clear risk that the military technology or equipment to be exported might be used in the commission of serious violations of international humanitarian law” according to Criterion 2 of the Common Position and to authorize the export.

EU member states should not limit their refusals to violations of IHL which are actually proven beyond any doubt, but should treat the risk of such violations as a ground for refusal. The ICRC advice on applying IHL criteria in arms transfers decisions states:

Common position: more grounds

Other criteria from the Common Position provide grounds to refuse export licences to the coalition members as well.

The 4th criterion concerning “Preservation of regional peace, security and stability” focuses mostly on agression against another country. As the intervention of the coalition is formally based on invitation by the internationally recognized government of Yemen and to aid this government, a narrow interpretation of this criterion may seem not to pose a problem for authorizing exports.

A narrow interpretation of the 3rd criterion can lead to a similar conclusion. This criterion concerns the “internal situation in the country of final destination, as a function of the existence of tensions or armed conflicts”. The Common Position states that “Member States shall deny an export licence for military technology or equipment which would provoke or prolong armed conflicts or aggravate existing tensions or conflicts in the country of final destination.” As the conflict in Yemen is an internal conflict in a neighbouring state and not in the country of destination, such narrow interpretation can lead to a positive decision concerning an export licence.

A different conclusion can be drawn when both criteria are considered together and when broader elements are considered, such as “the need not to affect adversely regional stability in any significant way” of criterion 4. The intervention by the coalition has not brought more stability or security in any way, nor is there any perspective it will do so in the future. Rather, it has worsened the situation for the civilian population and created the largest humanitarian disaster of today. The intervention seems to lead to a further division and fragmentation of armed groups. Furthermore, it causes a massive inflow of arms and uncontrolled diverting of arms.

In fact, a large amount of exported small arms and light weapons, munitions and armoured vehicles had Yemen as country of final destination. In other words, authorizing further exports to coalition members would lead to a prolongment of the conflict in Yemen. While these criteria leave more space for diverting interpretations and conclusions, any serious consideration has to take into account the humanitarian impact and the risk of prolonging the ongoing conflict in which the destination countries participate. Such consideration makes it difficult to understand how arms exports to the coalition members could and can still be authorized by EU member states.

Criterion 7 concerning diversion should also lead to a negative conclusion concerning arms export licences, especially concerning small arms and light weapons, munition, armoured cars and any equipment which can be used by any of the militias fighting in Yemen. Both Saudi Arabia and the UAE have been transferring such military equipment to the Yemen government troops as well as to a range of militias active in Yemen during the whole conflict. These transfers are not isolated incidents, but rather part of an ongoing process of support, training and cooperation with these armed forces. These armed forces and militias have not been considered as final destination during the export licensing process. Furthermore, both countries have a history of diverting weapons, e.g. to militias in Syria. It is also clear that both countries are not able to retain control over the diverted weapons. Diverted weapons of European origin have been observed on the black market in Yemen. Some of this military equipment even showed up in the hands of AQAP. Therefore there is a clear risk of diversions as mentioned in Criterion 7 of the Common Position, which should lead to a refusal of export licences.

image: Alisdare Hickson [CC BY-SA 2.0]

EU arms export regulations: ignored by EU member states.

As illustrated by the discussion of criterion 3 and 4, the Common Position still leaves room for improvement as situations arise which were not foreseen. However, the main problem is the implementation of this Common Position by the EU member states.

On 16 September 2019 the Council of the European Union adopted its conclusions on the review of Common Position 2008/944/CFSP. It recalls its commitment to strengthening the control on the export of military technology and equipment, to convergence of such arms export policies and to “the setting, upholding and implementation of high common standards” for such transfers by member states. It also “welcomes Member States’ renewed commitment” to the slightly amended Common Position.

However, this is all a fairy tale. The actually existing arms export policies of the EU member states show no commitment to or upholding or implementation of high common standards. On the contrary, these export policies show a strong disregard of the criteria of the Common Position, as this reports illustrates for the Yemen case.

Some EU member states have started to restrict arms trade to Saudi Arabia and the UAE.4

Belgium shows a mixed policy due to the regionalisation of arms trade competences. Flanders has not approved licences to Saudi Arabia or the UAE anymore since 2016. The Walloon region on the other hand states that it will take the criteria of the Common Position into account for new contracts with Saudi Arabia, which implies that licences for ongoing contracts will still be approved despite the earlier cancellation of some licences by the administrative court.

The Netherlands announced in March 2018 it would no longer authorize licences for arms exports to Saudi Arabia, unless it could be proven that they would not be used in the Yemen War. At the end of 2018 this restriction was extended to the UAE, and temporarily also for Egypt.

The murder of Jamal Khashoggi in October 2018 triggered some EU member states into restricting arms trade with Saudi Arabia. Denmark and Finland announced to no longer approve any new arms export licences to Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Germany halted direct export since November. However, after protests from France and the UK, exports for joint projects remained possible when proven that the material was not used in the Yemen war. Italy ended the export of aircraft bombs and missiles in 2019 to Saudi Arabia and the UAE after a parliamentary resolution.

Other EU member states, which are active in the arms trade, have thus far proven unwilling to end or restrict arms exports to Saudi Arabia, the UAE and other active coalition participants. The UK government contests a High Court decision blocking exports and has even ignored the ban on new licences by the court.

This overview shows that EU member states have only very recently taken the war in Yemen into account, if at all. When restrictions do arise, they rarely seem to result from a thorough assessment according to the Common Position, but seem to have been taken for political reasons. Therefore, the conclusion remains that EU member states in general are ignoring and violating their obligations under the Common Position 2008/944/CFSP and under article 6 and 7 of the Arms Trade Treaty.

The current situation shows a very diverging practice concerning export licences. The Common Position may be a common legally binding framework, the practice is far from common. The intended objective “to promote convergence in the field of exports of military technology and equipment within the framework of the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP)” (preamble (5)) is far from a reality. At the same time such convergence is needed when the European arms industry is getting increasingly integrated. The production of large weapon systems mentioned in this report is generally based on supply chains which are not limited to the exporting state but stretch across the EU. All the more reasons to ensure that the Common Position is respected as the minimum standards (preamble (3)).

image: Alisdare Hickson [CC BY-SA 2.0]

Recommendations

Our recommendations start therefore with the basic demand to apply and enforce the binding legal rules which already exist. The first and obvious recommendation is to apply the Common Position 2008/944/CFSP in a strict manner, including by reviewing ongoing licences when circumstances change.

More specifically, this implies to end the export of military materiel and the provision of military assistance to Saudi Arabia and the UAE, as well to other coalition members in line with their involvement in the Yemen war.

Given the facts, it is clear there is a problem with the compliance of the EU member states with the existing legal framework and with the enforcement of these minimum standards towards them. The logical conclusion is that the compliance with the rules of the Common Position has to be made enforcable towards the Member states. Other actors need to be able to realise this enforcement.

As such, the competence to decide whether to grant export licences can remain with the EU member states at the national level. EU member states have the full competence to decide about licences or measures in a wide range of policy areas, like environmental law, consumer law or internal market law. However, their actions need to be in conformity with the minimum standards set at the EU level. If a member state ignores these minimum standards or rules, other actors (ranging from the European Commission to NGOs) can demand the courts to enforce these minimum standards. There is no reason why such enforcement should not be possible for rules concerning arms exports.

Currently Common Position 2008/944/CFSP may be legally binding, but it can be ignored without consequences by member states. This is due to the fact that a Common Position, although legally binding for the member states, belongs to the intergovernmental CFSP norms for which neither the European Court of Justice nor the national courts have jurisdiction to review implementation and compliance. National courts can review arms exports decisions only insofar as the rules of the Common Position have been integrated into national law.

Common Position 2008/944/CFSP could be made enforcable by including its rules into another EU legal instrument which provides jurisdiction to the European Court of Justice and the national courts. Including the content of the Common Position 2008/944/CFSP into a directive would not change the competences of the EU member states. However, it would allow legal review of the implementation of these rules in export laws and of the compliance of arms export decisions with these rules. Enabling such review by the courts on the initiative of other actors (which also entails a stronger and timely transparency concerning the existence of arms export licences, the arms exports they cover and of the evaluation process and motivation of the decision concerning the licence) is a necessary step to ensure the enforcement of minimum standards in arms export law and the implementation of Common Position 2008/944/CFSP.

Footnotes

- Report of the detailed findings of the Group of Eminent International and Regional Experts on Yemen - Situation of human rights in Yemen, including violations and abuses since September 2014, A/HRC/42/CRP.1, par. 913, p. 218-219. See also the ICRC commentary to article 1 common to the Geneva Conventions, 2016, para. 162; ICRC, “Arms Transfer Decisions: Applying International Humanitarian Law Criteria”, Practical Guide, May 2007 (https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/assets/files/other/icrc_002_0916.pdf); .

- Report of the detailed findings of the Group of Eminent International and Regional Experts on Yemen - Situation of human rights in Yemen, including violations and abuses since September 2014, A/HRC/42/CRP.1, par. 916, p. 220.

- ICRC, Arms transfer decisions: Applying international humanitarian law criteria, 2007, p. 9

- This overview is based on https://urgewald.org/Jemen